Why Do Thousands of Animal Species Thrive in a Single Patch of Soil?

By Dr. Ting-Wen Chen, The University of Göttingen (Germany) and National Chung Hsing University (Taiwan)

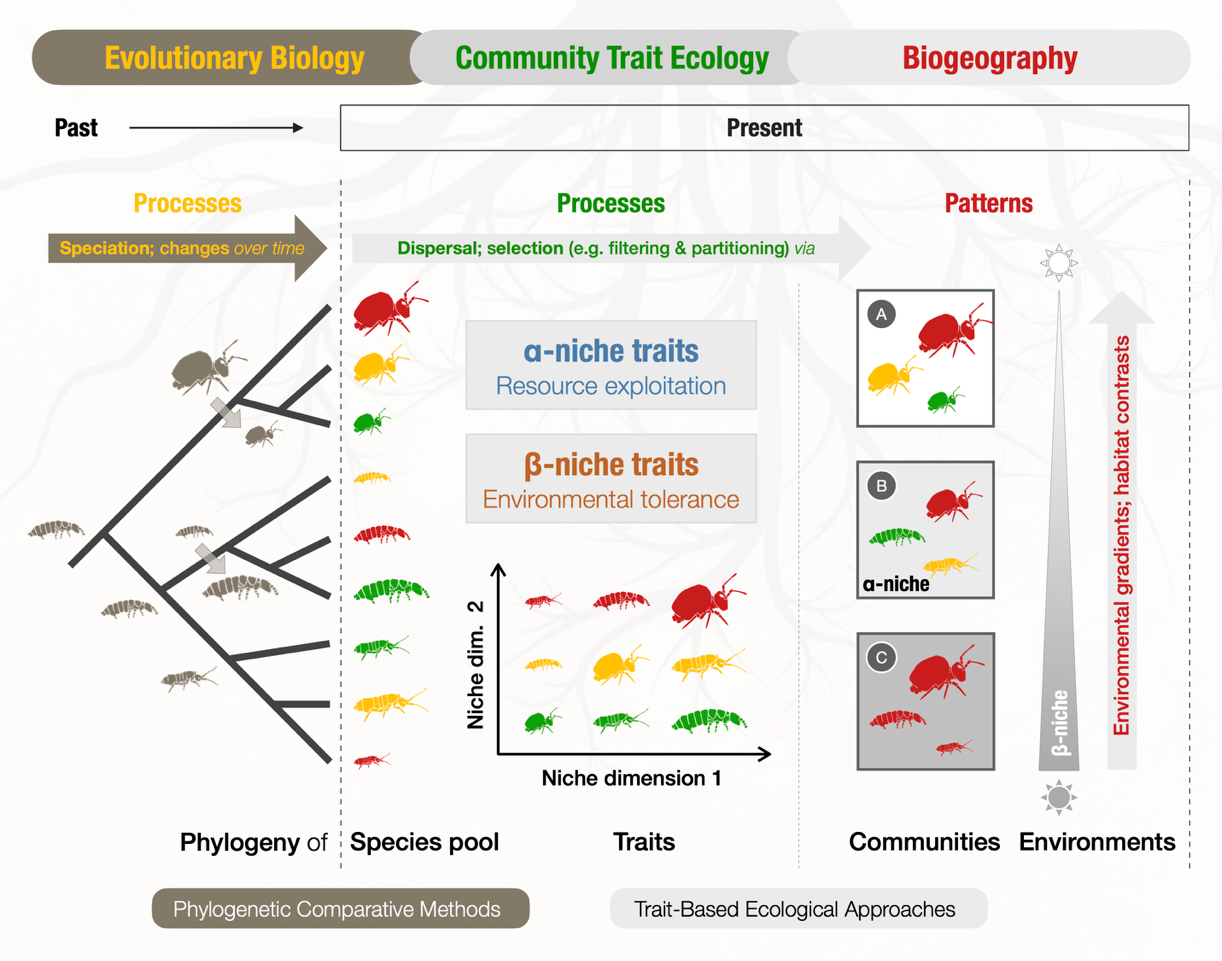

Figure 1: The "Community-Trait-Phylogenetic Ecology” (CTPE) Framework for studying soil animal diversity. The CTPE framework integrates ecological and evolutionary processes to understand mechanisms driving soil biodiversity across scales (https://doi.org/10.32942/X2W07B)

Fifty years ago, British ecologist J.M. Anderson asked a deceptively simple question: How can a single square meter of forest soil support thousands of animal species comprising millions of individuals? Soil’s hidden world is astonishing. Within one square meter of forest litter, 10,000 to 200,000 tiny animals (called mesofauna) belonging to 60–200 species can be found. Springtails (Collembola) and oribatid mites dominate, making up 95% of all soil arthropods. Even though these animals share space and often eat similar things, hundreds of species coexist without obvious conflict. How is this possible?

Traditionally, soil ecologists and zoologists have firstly approached this puzzle by species-based approaches looking at which animals live where based on environmental factors. This method maps biodiversity patterns but doesn’t explain why such patterns emerges. Then, the functional trait approaches use some attributes of soil animals (e.g. their size, shape, or diet) to predict coexistence but miss the role of evolutionary history. Phylogenetic comparative approaches have shown that related species inevitably tend to resemble each other in their traits, resulting in patterns of “phylogenetic signal”, but for most soil biologists, ecology and evolution are often treated as separate research domains. Each view is useful to solve the mystery, yet incomplete.

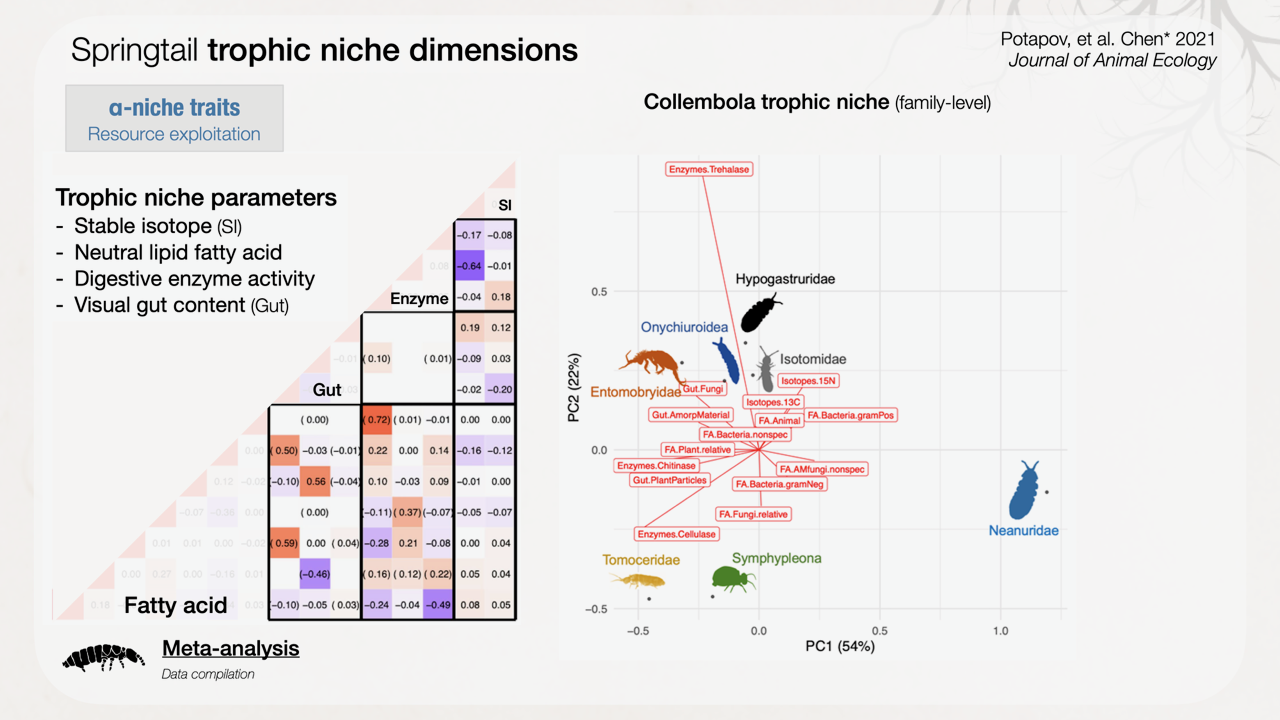

Figure 2: Multidimensional α-niche traits of springtails represented by trophic parameters including stable isotopes, neutral lipid fatty acids, digestive enzymes and visual gut contents that provide complementary food resource information (https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.13511)

To bridge these perspectives, I am developing an integrative “Community–Trait–Phylogenetic Ecology (CTPE)” framework for soil animal research. It views soil biodiversity through three connected lenses: (1) Biogeography, which describes diversity patterns across gradients from local to global scales; (2) Functional traits, which represent two types of niches (α-niche, resource use, and β-niche, environmental tolerance) and help infer complementary assembly processes such as filtering and partitioning; (3) Phylogeny, which captures the evolutionary history of species and their traits, setting the species pool for contemporary community assembly.

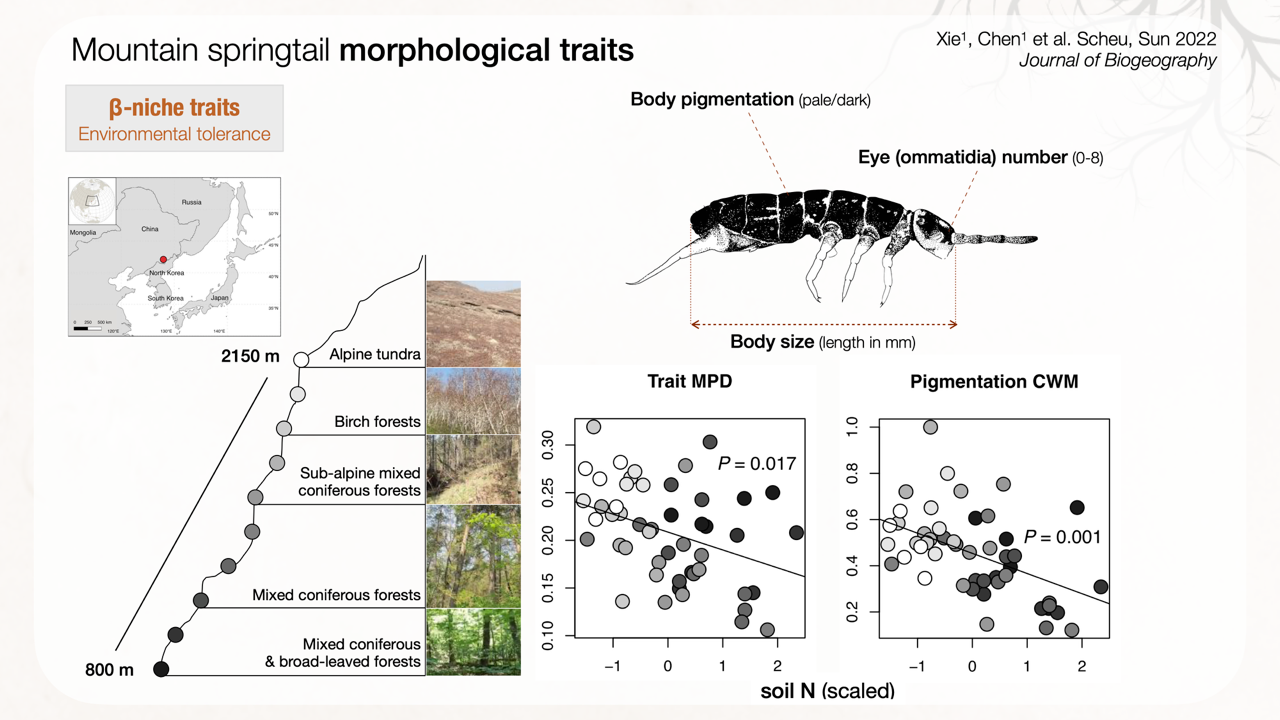

Figure 3: Isotomid springtail community β-niche traits represented by morphological traits (pigmentation, ommatidia number and body size) collected from 800 m to 2150 m asl of Changbai Mountain, Northeast China. Soil nitrogen (N) concentration predicts trait mean pairwise distance (MPD) and pigmentation community-weighted mean (CWM) of coexisting species ( https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14317)

Real-world studies on springtail communities illustrate how the CTPE framework works. In global datasets, the density of springtails does not predict species richness, yet their community traits vary strongly with habitat type, latitude, biome, and local density. In Northeast Asia’s Changbai Mountain, ancient and newly evolved springtail lineages coexist, and communities shift in pigmentation along elevation gradients. At the local scale, analyzing multiple traits at once shows that both filtering and partitioning processes operate within the same springtail community, depending on which traits are operating. In addition, cryptic springtail species, which diverged millions of years ago, can coexist locally while showing distinct habitat preferences.

Why does this matter? As climate and land use change across the globe, understanding both the evolutionary roots and ecological dynamics of soil communities becomes crucial for conserving biodiversity and the ecosystem functions we depend on. Protecting soil biodiversity means safeguarding not only species but also their roles and evolutionary distinctness. Fifty years after Anderson’s question, we now have new tools, theories, and frameworks. Soil is no longer a black box but a kaleidoscope revealing the hidden wealth of life beneath our feet.