Soil Biodiversity–Ecosystem Functioning (sBEF): The More, the Better?

Dr. Alejandro Berlinches de Gea (Wageningen University, Netherlands)

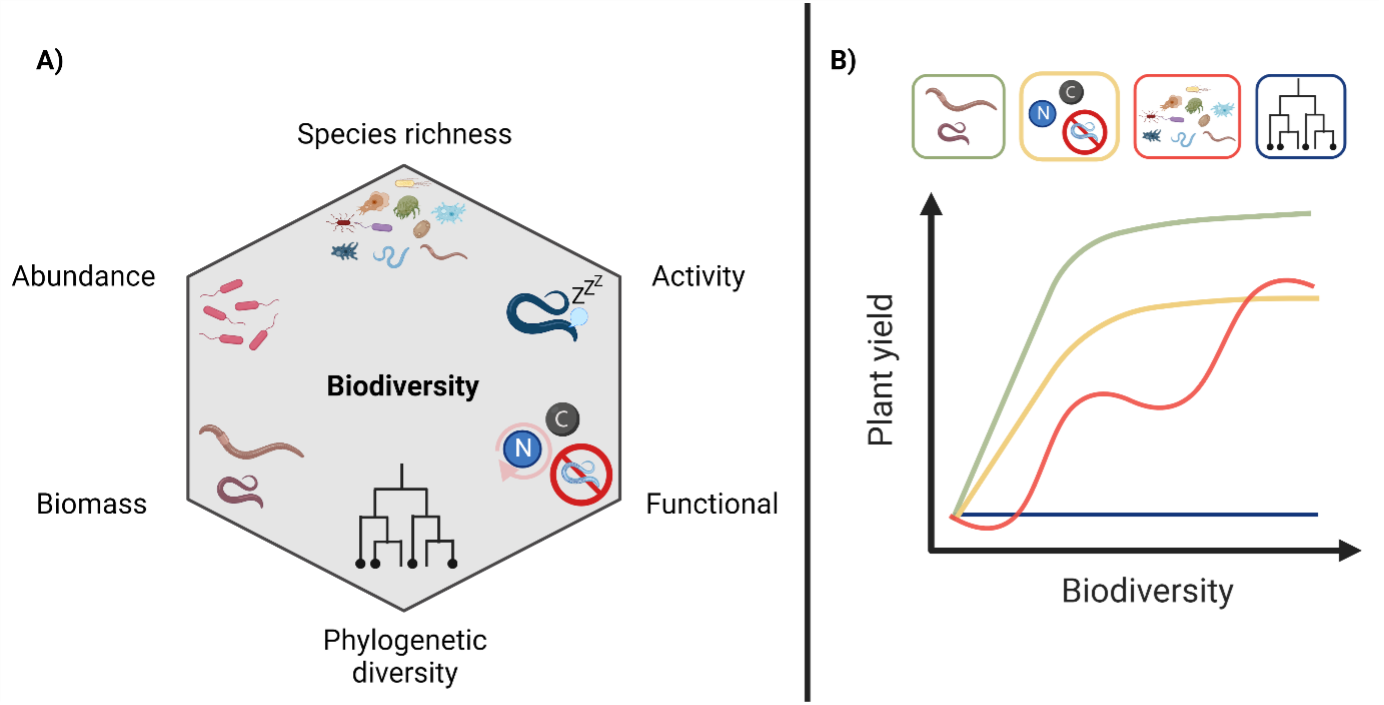

(a) Conceptual illustration of the different facets of soil biodiversity that underlie soil biodiversity and ecosystem functioning (sBEF). (b) Hypothetical representation of the sBEF link depending on the biodiversity facet considered. The icons on top are related to the functions depicted by having the same color and are the same as in (a), representing biomass, functional diversity, species richness, and phylogenetic diversity as four different biodiversity facets.

(https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/gcb.16471)

Andy Hector and Rowan Hooper, in 2002, revisited what is often considered the first ecological experiment. Originally described by Darwin in The Origin of Species, it dates back to 1826, when the Duke of Bedford’s head gardener tested how individual plant species and their mixtures performed. The outcome was clear: more diverse plant communities were more productive. Today, this idea is known as the Biodiversity–Ecosystem Functioning (BEF) concept stating that increasing biodiversity will enhance ecosystem functioning. But what happens when we move to soils, the most diverse ecosystem on Earth? In such a system with millions of organisms in a single teaspoon of soil, does adding or removing a few species still matter? And if a soil BEF (sBEF) relationship exists, is it always positive, or does it depend on environmental context and/or biodiversity indexes measured?

These questions form the core of my research. During my time at Wageningen University, under the supervision of Stefan Geisen, we tackled them using manipulative experiments that allowed us to directly control soil biodiversity under different global change drivers. By actively assembling soil communities with different levels of diversity, we could test whether increasing biodiversity truly benefits plants—or whether its effects depend on environmental conditions.

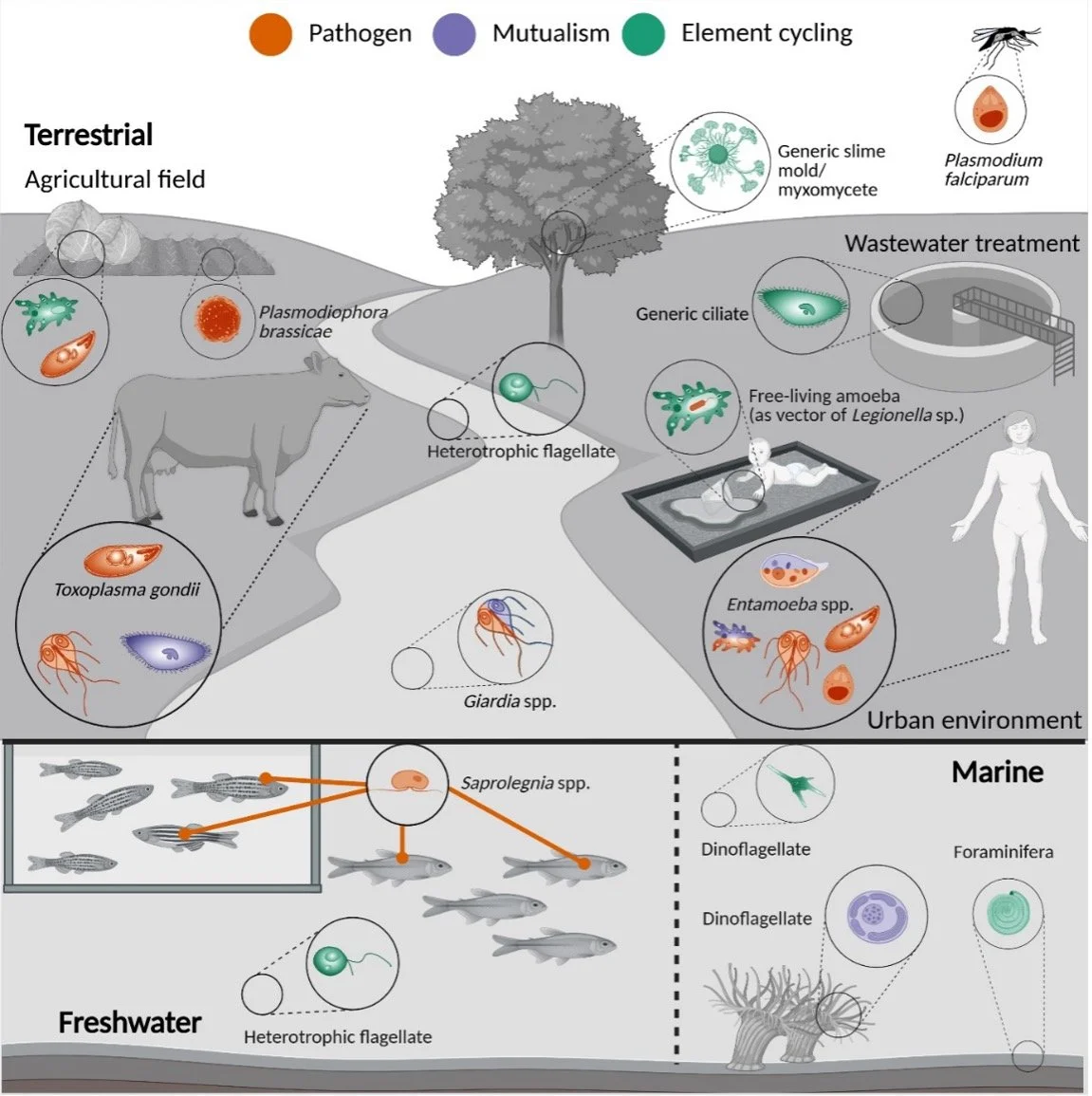

“Visual representation of the different roles that protists play in One Health in terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystems” (https://academic.oup.com/ismej/article/19/1/wraf179/8239679)

To do so, we focused on a fascinating and often overlooked group of soil organisms: protists. Protists are unicellular eukaryotes that are neither plants, animals, nor fungi, yet they span the vast majority of the eukaryotic tree of life. Their extraordinary taxonomic diversity is matched by their functional versatility. Protists can perform different ecological functions such as pathogens, mutualists, or nutrient cycling—and some species switch roles depending on their life stage or environmental conditions. Predatory protists, in particular, play a central role in soil ecosystems. By predating mainly on bacteria and fungi, they shape the soil microbiome, release nutrients that plants can readily take up, and suppress pathogens either directly or indirectly. This process, known as the microbial loop, positions protists as key regulators of soil ecosystem functioning and ideal candidates for testing sBEF.

Experimental setup in a greenhouse at Wageningen University. Here we were testing the effect of increasing soil microbiome predator diversity (protist and nematodes) on plant performance under the influence of interacting global change factors.

As often shown by ecologists, our results reveal a strongly context-dependent sBEF relationship. An increasing protist diversity had neutral effects on plant performance under control conditions, positive effects when pathogens were present, and negative effects under drought. We also examined whether higher protist diversity could reduce the need for nitrogen (N) inputs. Rather than substituting fertilization, protist diversity and N acted complementarily: protists enhanced plant growth by restructuring bacterial communities, while N inputs mainly influenced plant nutrient content. Finally, when multiple global change drivers co-occurred, unpublished results suggest that soil microbiome predators may help sustain plant performance under increasing environmental stress. Thus soil biodiversity, especially protist, is essential for ecosystem functioning, but it is strongly dependent on the environmental changes driven by global change. If this has sparked your curiosity about protists and sBEF, stay tuned—there is still much to discover beneath our feet.