Assessing Soil Biodiversity: When to Use Which Method to Measure What?

Dr. Julia Köninger (University of Vigo, Spain)

Julia looking for macrofauna from a soil monolith in an urban park.

While it is quite clear how important soil biodiversity is as the cradle for terrestrial biodiversity and for the wellbeing of humans, measuring it still causes many open questions. This is not necessarily becoming easier having more methods at hand. Over the last years, many researchers switched from morphological ways of studying soil life using the microscope or the magnifying glass to cheaper, less taxonomic expert-dependent molecular methods, analysing the DNA found in soils (environmental DNA, eDNA).

Julia taking an auger composite sample for DNA and nematode analysis at a Spanish wetland site.

My own path, however, went against this trend. In my PhD, I learned mostly about eDNA while working with the first Europe-wide sampling for eukaryotic DNA including eukaryotic microorganisms such as protists and fungi, along with soil fauna such as nematodes, arthropods and annelids. The 778 samples gathered through the LUCAS Soil survey allowed to compare the diversity in different ecosystems. Back then, I found surprisingly higher diversity in croplands compared to grass- and woodlands. It was not only me finding such results, but many other eDNA studies pointing in the same direction, also when looking at bacteria or archaea. But which story of soil life are molecular methods telling? In a recent study, we compared eDNA results with those of other EU-wide studies assessing soil fauna using morphological methods. What we found was that molecular methods tell a different story than morphology-based methods which are linking higher diversity to less intensive land use. These striking discrepancies raise a fundamental question for soil ecologists: which methods do you use for which purpose, especially when it comes to assessing soil life? Using eDNA you need to keep biases in mind arising from relic DNA of animals (necromass) that previously lived rather than currently live in that soil. Also, you might find many more cryptic species difficult to capture when extracting the animals from soils using heat, light or water or looking for them in soil monoliths causing discrepancies.

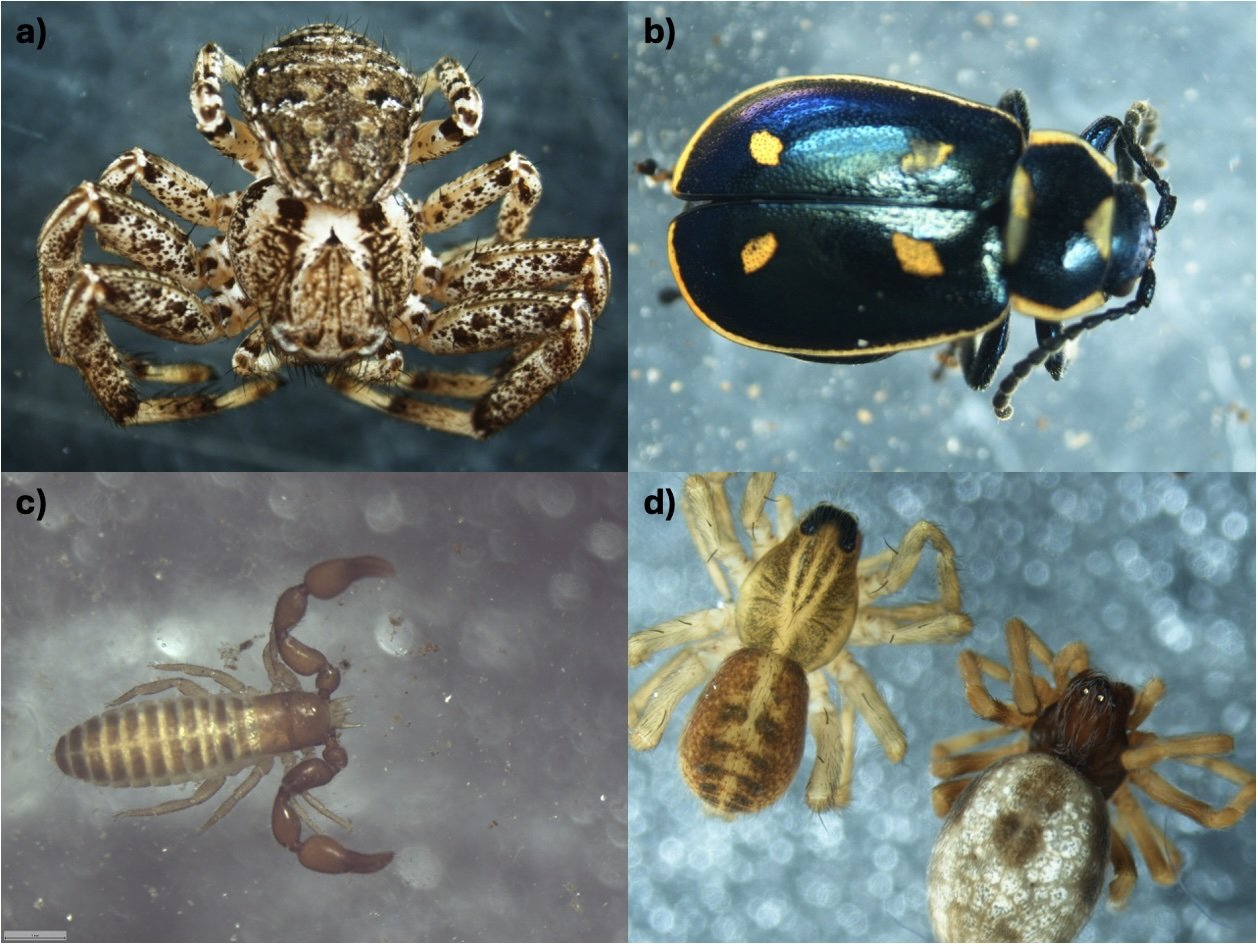

Macrofauna under the magnifying glass from the SOB4ES sampling: a) crab spider (Thomisidae), b) Eriopis (Coccinellidae), c) Pseudoscorpion (Chernetidae), d) wolf spider (Lycosidae) on the left and orb-weaver spider (Araneidae) on the right.

Consequently, it is crucial to consider the purpose of your study and the method to assess soil biodiversity - particularly in terms of National/Continent-wide monitoring schemes. They often rely on molecular methods to assess soil biodiversity as a first and feasible measurement such as the European Soil Monitoring and Resilience Law that was formalized in 2025, requiring Member States to monitor bacteria and fungi as a minimum. Soil fauna, however, probably will remain neglected in many monitoring schemes. Here, it is crucial that widely applied molecular methods require cross-validation and improving e.g. by filtering out necromass or by considering larger soil volumes. This is one of the goals of my post-doc, where I analyze soil fauna across spatial and temporal gradients from wetlands, urban sites, woodlands, grasslands and croplands using morphological as well as molecular methods.

Julia visited by a curious bush cricket.

More insights into my work and probably many photos of beautiful soil dwellers will be presented at the GSB conference in Canada – looking forward seeing you there!